Forget BlackBerrys or wedges: the most desirable accessory for huge numbers of adolescent girls today is a cigarette. The trend began in the 1990s, when girls started to overtake boys as smokers; the gap grew to10 percentage points in 2004 with 26% of 15-year-old girls smokingcompared with 16% of boys. The gap has narrowed since but in 2009 girls are still more likely to smoke than boys.

There has long been a synergy between the changing self-image of girls and the wiles of the tobacco industry. Smoking was described by one team of researchers as a way in which some adolescent girls express their resistance to the "good girl" feminine identity. In 2011, when Kate Moss creates controversy by puffing away on the Louis Vuitton catwalk and Lady Gaga breaks the law by lighting up on stage, cigarettes have clearly lost none of their transgressive appeal.

What's different today is the "dark marketing" techniques used by the tobacco industry since the demise of "above-the-line" advertising in 2002. These appeal to girls' fears and fantasies, through subliminal online and real-world sponsorship.

Tobacco manufacturers, for instance, have been accused of flooding YouTube with videos of sexy smoking teenage girls, while in a pioneering partnership with British American Tobacco, London's Ministry of Sound nightclub agreed in 1995 to promote Lucky Strike cigarettes. Most pernicious because they are the most covert, though, are the underground discos organised by Marlboro Mxtronic and Urban Wave, the marketing wing of Camel. Beneath the Camel logo, Urban Wave dance parties – stretching from Mexico to the Ukraine – hand out free cigarettes, and are themselves free: you must be invited and register, thereby helping the tobacco company build up a database. In the US a 2007 fashion-themed Camel 9 campaign was clearly targeted at young women, and so-called "brand stretching" has popularised tobacco brands on non-tobacco products, such as Marlboro Classic Clothes.

Adolescent girls seem particularly susceptible to the blandishments of the tobacco industry. Susie, 15, began smoking two years ago. "It was on the common and everyone started experimenting. You think, 'Ooh, I'm more cool, ooh I'm smoking I feel grownup and in with the crowd.'" Vanessa, 15, remembers that "it gave me a headrush, and it impressed my friends". Becca, 21, became a regular smoker at 15. "We were going out and lying about our age and thought smoking made us look older."

Janne Scheffels, a Norwegian researcher, argued recently that teenage girl smokers view it as a kind of "prop" in a performance of adulthood, a way of crossing the boundary between childhood and adolescence, and moving away from parents' authority. Becca, says: "It felt like getting one over my parents: the fact that they didn't like it and couldn't stop it made me feel better."

Teenage smokers, the theory used to go, suffer from a lack of self-esteem (the so-called deficit model). The reality is more complex. Asuccession of studies have found that smoking positions you in a group of "top girls" – high-status, popular, fun-loving, rebellious, confident, cool party-goers who project self-esteem (not, of course, the same as actually having it). Non-smokers are mostly seen as more sensible and less risk-taking.

Smoking, says Vanessa, is also bonding. You start conversations with strangers when you ask for a light – an attractive social lubricant for awkward teenagers. But the hub of teen smoking is break-time: it builds a girl's smoking identity. Sara, 14, says: "That was when it became regular, when I started going out at lunch and break, round the corner from school where everyone smokes. You become less close to people who don't go out."

Some smoke for emotional reasons: smokers are more likely to be anxious and depressed; having a cigarette is a way of dealing with stress. Twice as many teenage girls suffer from "teen angst" as boys,according to a report from the thinktank Demos last month.

According to Amanda Amos, professor of health promotion at the University of Edinburgh, there's also a social class dimension: more disadvantaged teenage girls smoke, and they're less likely to give up. Then why aren't boys equally affected? This is where it gets particularly dispiriting. "Top boys" have alternative ways of displaying prestige, such as sport: smoking to look cool conflicts with their desire to get fit. Girls want to be thin more than fit: smoking, they believe, helps keep their weight down. One in four said that smoking made them feel less hungry and that they smoked "instead of eating".

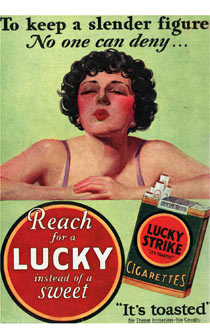

An ad that sells cigarettes as a slimming aid for young women. Photograph: Getty

An ad that sells cigarettes as a slimming aid for young women. Photograph: Getty

Already in the 1920s the president of American Tobacco realised he could interest women in cigarettes by selling them as a fat-free way to satisfy hunger. The Lucky Strike adverts of 1925, "Reach for Lucky instead of a sweet", one of the first cigarette advert campaigns aimed at women, increased its market share by more than 200%. Between 1949 and 1999, according to internal documents from the tobacco industry released during litigation in the US, Philip Morris and British American Tobacco added appetite suppressants to cigarettes.

The industry has continued to exploit girls' and women's anxieties about weight. Since advertising was banned, says Amos, packaging is one of the few ways that tobacco companies can communicate with women. Young women looking at cigarette packs branded "slim" are more likely to believe that the contents can help make them slim. So no prizes for guessing the target market for the new "super-skinny" cigarettes – half the depth of a normal pack of 20 – like Vogue Superslims, or the Virginia S (new packaging: black with pink trim).

Until recently, few health education campaigns had taken on board the research into why young women smoke and so – unsurprisingly – had little impact. Some even inadvertently encouraged smoking: if you bang on about how bad cigarettes are you make them – to this group – sound good. And there's no point in trying to scare girls about developing cancer when they're old: they don't think they will be.

The ones I interviewed know the health risks but use all kinds of strategies to exempt themselves: their uncles smoke and are fine; they'll stop when they're pregnant (they disapprove of smoking pregnant women); they'll stop to avoid wrinkles; they'll stop when they're "20 or 30".

The successful campaigns have been radically different. The brilliant late-1990s Florida "truth" campaign, eschewing worthy public health appeals, played the tobacco industry at its own game. Through MTV ads, a tabloid distributed in record shops, merchandising, and a "truth" truck touring concerts and raves, it attacked the industry for manipulating teens to smoke, repositioning anti-smoking as a hip, rebellious youth movement. As a result, the number of young smokers declined by almost 10% over two years.

It doesn't do to get morally panicky about girls and smoking. For one thing, now that – in year 10 – "everyone smokes", non-smokers and other independent-minded girls are acquiring a cool of their own. Smoking to look cool, it's even been suggested, risks you being judged a "try-hard".

On the other hand, cancer is the greatest cause of death among women and, as Amos points out, we haven't seen the full health consequences of this bulge of girls' smoking yet. Last week Amos addressed the European parliament as part of Europe Against Cancer Week. Female MEPS were shocked when she passed round packets of super-skinnies clearly targeted at girls, and discussed how women need to be empowered not to smoke. Girls need alternatives that make them feel as powerful, independent and attractive as they think cigarettes do. Smoking really is a feminist issue.